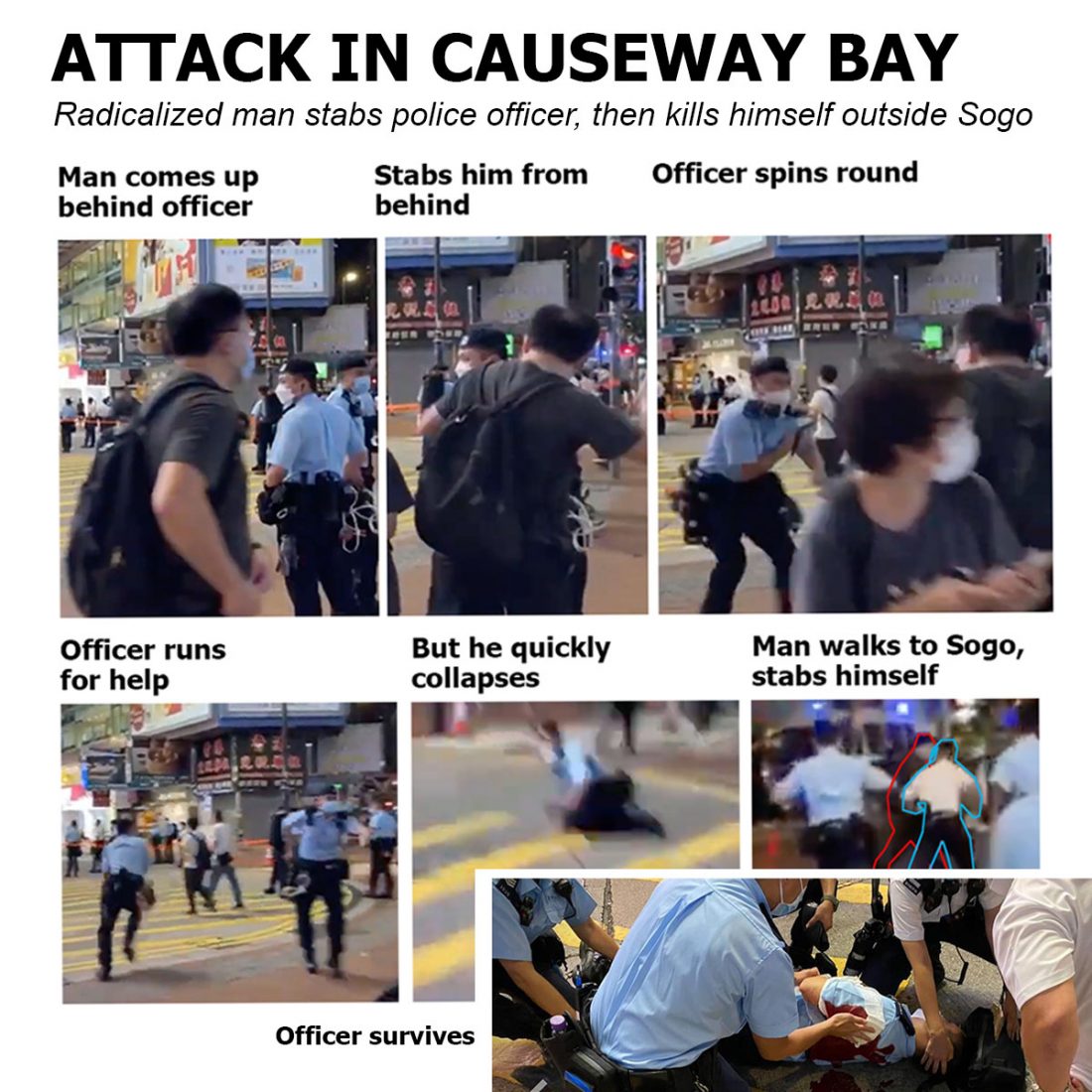

A YOUNG POLICE OFFICER is approached from behind and stabbed by a politically radicalized man who then commits suicide. It’s a classic terrorism scenario.

It happened in Hong Kong on July 1st, and the stab victim, 28, was gravely wounded but survived.

On the Internet, Twitter exploded into life.

“It’s a real pity that the officer didn’t die,” said Tak.

“HK police lives don’t matter,” said PK.

“You get what you f***ing deserve,” said Ayan.

“Ha ha ha ha” said Benis. “I hope you all get it.”

“I hope more popo will get stabbed,” said CCPFight.

Anyone scrolling through Hong Kong-related tweets cannot help but encounter these shocking messages glorifying a horrific attempt on the life of a random police officer, caught on video.

Kill more efficiently

Worse still, many of the writers called for more attempted murders or even offered advice on how to kill police officers more efficiently.

“Surely the first of many . . . No Hong Kong cop is now safe,” said Memes.

“Next time you stab a collaborating CCP thug, get his heart or his head,” said Andrei Markovich.

Police arrested two individuals for inciting others to kill police officers or burn down police premises – but scores of other similar comments went unpunished.

Glorifying the attacker

A third strand of comments glorified the knife attacker, who apparently chose his young victim at random.

“Wonderful, good job, RIP,” said Jason.

“The man who sacrificed himself must deserve the greatest honor,” said DYeung13.

“RIP Hong Kong hero,” said realhker.

“Mourn the martyr of Hong Kong”, said Vincent Wong.

These were accompanied by media reports accusing police of “harassing” flower-carrying individuals who “had a right” to salute the man who tried to commit murder.

Shifting the blame

There was also a fourth strand of comments. This consisted of rather desperate comments in which individuals who had dedicated themselves to radicalizing people against the authorities, tried to shift the blame back to the authorities.

“The despair and desperation caused by the Chinese communist party is clear, palpable and devastatingly tragic,” wrote tireless ideologue Benedict Rogers of the UK.

Also shifting the blame was another dedicated cultivator of anger, Denise Ho of Oslo Freedom Foundation fame, a US-based “revolution consultancy”.

She bizarrely appeared to try to blame the attempted murder on the US-style national security law introduced in Hong Kong a year ago.

“The despair one must undergo to resort to such an extreme act. What has Hong Kong become, only within one year?” she wrote.

Inhuman delight

Naturally, the critics of the anti-government lobby have expressed horror at the way some people have taken an inhuman delight in a clearly despicable crime.

But it’s important that we don’t assume that the vile voices quoted above represent all or even the majority of protesters.

The number of “likes” the nastiest comments attract is relatively low, the number of “mourners” was just a small crowd, and Hong Kong, even after the polarization of 2019, remains a low-crime, low-violence city.

Is it a crime?

But here’s the issue. A terrorist act, such as attempted murder of a police officer for a political reason, is clearly a crime. But is glorification of such an act also a crime? Should the authorities stop people beatifying the perpetrator?

In discussions, this writer has heard it said that mainland China would criminalize such comments, but Western countries wouldn’t.

In fact, this is quite incorrect. Glorifying terrorism is considered an offence world-wide. If you have publicly promoted terrorism using your real name, you should consult a Hong Kong lawyer specializing in that area of the law. For a more general summary of the actual situation, read on.

A global crime

The United Nations Security Council in 2005 agreed that nations should repudiate, in law, “attempts at the justification or glorification of terrorist acts that may incite further terrorist acts.”

The regulation, known as Resolution 1624, was drafted by the United Kingdom. It was quickly passed by the entire United Nations council. No countries voted against it, and no countries abstained from the vote.

However, the actual drafting of specific laws for each country were left to the countries themselves. As a result, there were a range of interpretations. We’ll consider some representative examples below.

UK moves fast

Some countries acted quickly. The UK’s Terrorism Act 2006 made it an offence to publish a statement which “is reckless as to whether members of the public will be directly or indirectly encouraged or otherwise induced by the statement to commit, prepare or instigate such acts or offences.”

Unlawful already

Others said it had such laws. New Zealand said it had been unlawful since 1993 to publish or distribute “words which are threatening, abusive, or insulting” or “likely to excite hostility against or bring into contempt any group of persons . . . on the ground of . . . political opinion.”

Mixed results

Others had trouble implementing the law. In the United States, the right to freedom of political speech is almost absolute. All types of offensive speech, including hate speech, and all political speech, is protected by the First Amendment. Interference may only be allowable in cases of imminent danger.

However, neighboring Canada successfully amended its Criminal Code in 2015 to create a new offence that criminalizes the advocacy or promotion of the commission of terrorism offences in general.

Always two reactions

One last point: Many people, with a range of political views, have expressed disappointment at Hong Kong people in general at the praise for the attacker and lack of sympathy for the young police victim.

This is understandable. Yet it’s worth making the point that police officers have been randomly stabbed or attacked in political incidents in Western countries (often involving Islamist radicals), and there are always two types of reaction.

The vast majority of the public is horrified, while a small number of pro-violence radicals (in practice, other Islamists) rejoices. Hong Kong is no different, in broad terms.

What is perhaps unusual in Hong Kong is the media support for people wanting to mythologize as glorious a tragic incident, combining a heinous attempt to kill an innocent young man and a grim suicide.

The irony

Ironically, police who stop individuals from publicly expressing support for what appears clearly to be attempted murder, may be rescuing them from committing a United Nations-designated crime. Judging by the low number of arrests for incitement to murder or commit violence (only two at the time of writing) Hong Kong is policing with a light touch.

Nury Vittachi is editor of Fridayeveryday, a Hong Kong-based journalist and author, who gained fame through his witty comedy-news writing. He deviates from the conventional “journalistic” style and uses creativity to expand the meaning of journalism. His work does not just make you laugh, but reflect.

The story was published on Fridayeveryday, an English online platform that shares evidence-driven insights on Hong Kong and China.